Market Snapshot: Canada’s market and regulatory structures have kept Canadians well supplied with natural gas

Release date: 2017-07-18

Many liquefied natural gas (LNG) export projects are proposed for Canada, especially on Canada’s west coast. However, because of global oversupply of LNG and low LNG prices, none of these projects have been constructed and, as of June 2017, only one has decided to proceed.

Canada has exported a large share of its gas production to the United States (U.S.) for over five decades, yet Canadians have not had difficulties acquiring gas. The Canadian regulatory structure for approving gas exports and the structure of Canadian gas markets work together to keep Canadians well supplied.

Source and Description

Source: Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers and NEB (Production and Trade)

Description: This graph shows Canadian natural gas production, exports, and imports from 1947 to 2016. All values are in billion cubic feet per day (Bcf/d). Natural gas production increased from 0.1 Bcf/d in 1947 to around 7.0 Bcf/d in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Production continued to increase to a high of 17.5 Bcf/d in 2001, after which it dropped to around 13.9 Bcf/d in 2012, before increasing again to 15.1 Bcf/d in 2016. Exports closely followed this trend, increasing from 0 Bcf/d in 1947 to between 2 and 3 Bcf/d in the 1970s and early 1980s. Exports then increased to a high of 10.4 Bcf/d in both 2002 and 2007 before dropping to 8.1 Bcf/d in 2016. Natural gas imports remained at 0 Bcf/d until 1988 and then increased slightly to 0.2 Bcf/d by 2000. Imports increased further to between 2 and 3 Bcf/d from 2010 to 2016.

Regulatory Structure

Canadian companies require National Energy Board (NEB) and Governor in Council (GIC) approval to export natural gas, and must demonstrate to the NEB that the exports are surplus to Canadian needs. During the export license application process, other domestic market participants are provided an opportunity to comment on whether they believe the potential exports would prevent them from acquiring gas.

Meanwhile, Section 119 of the NEB Act allows the NEB, with approval from the GIC, to suspend or revoke export licenses if required. The NEB also monitors energy markets and publishes energy information so that Canadians are aware of how gas markets are evolving and can respond proactively if necessary.

Market Structure

Canadians have been well supplied with natural gas despite exporting large amounts for many years because of how Canadian markets are structured.

1) Integration: how well markets are connected through pipelines or other infrastructure

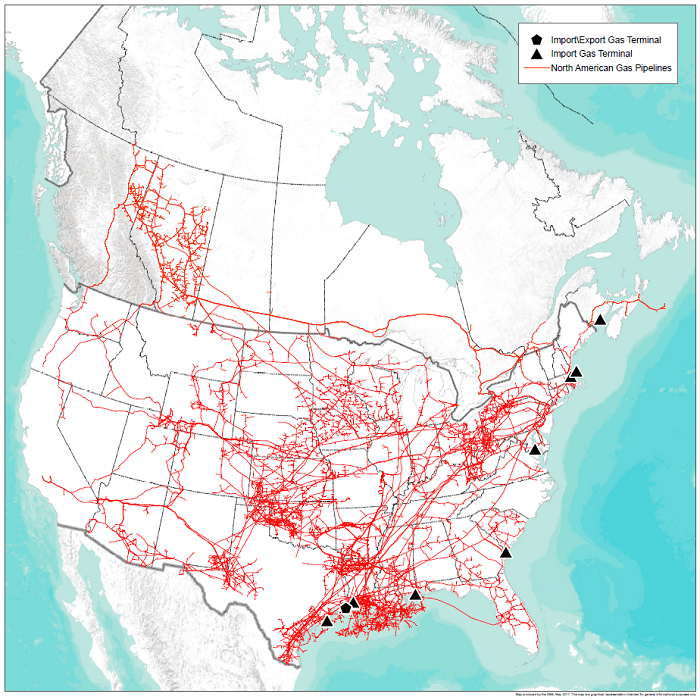

Canadian gas markets are well connected to U.S. markets via numerous pipelines (see map below). Therefore, when conditions change locally, the rest of the system across the continent adjusts to compensate. For example, higher gas demand in western Canada might cause less gas to be shipped to eastern Canada and/or fewer Canadian exports to the U.S. In response, eastern Canada could import more gas from the U.S. and/or U.S. markets could rely more heavily on their own gas.

Map of Major Canadian and U.S. Gas Pipelines

Source and Description

Source: NEB and EIA

Description: This is a map of major Canadian and U.S. natural gas pipelines. The Canadian pipelines extend from northeast British Columbia and northwest Alberta, through southern Saskatchewan and Manitoba, and into Ontario and Quebec. Pipelines also exist in New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, although these are not directly linked to the other Canadian pipelines. The network of U.S. pipelines connects with the Canadian pipelines at various points across the country. The U.S. network is spread over the entire U.S. but has hubs in the Midwest, Northeast, and Gulf Coast.

2) Size: overall market size and export volumes (i.e. how much gas is produced and consumed)

Canada produces 15 billion cubic feet per day (Bcf/d) of natural gas and currently exports about half of this. However, Canadian and U.S. gas markets are so interconnected that they are generally considered a single, continental market – the world’s largest at a combined 89 Bcf/d. Large markets tend to be more flexible, because changes in supply and demand tend to be relatively small compared to overall volumes. For example, current North American LNG exports, all from U.S. terminals, are about 1.7 Bcf/d (2% of market size) and do not have a significant impact on the overall market. Even if LNG exports rose to 7 Bcf/d, about the same as expected Australian exports in the 2016-17 fiscal year, this amount would still only be 8% of the combined Canada-U.S. market.

3) Transparency: availability of information that allows market participants to make informed decisions about buying or selling

Canadian and U.S. gas markets have numerous trading hubs where contracts are traded in large quantities and prices are publicly available. In addition, there is abundant, detailed information about the North American resource base (including studies done by the NEB) that underpins current and long-term gas production and market trends. As a result, market participants know what constitutes fair pricing for current gas production as well as where future gas supplies might be sourced.

4) Liquidity: how easily market participants can trade with each other

Canadian and U.S. gas markets have numerous participants active at many trading hubs. Thus, the average unit of gas is traded several times daily, and market participants have little difficulty finding counterparts with whom to trade. Storage is also abundant and plays a key role in balancing markets, especially heating demand, which changes depending on the season. Low heating demand in the spring, summer, and fall results in more gas being produced than consumed, and excess gas is injected into storage. During winter, when gas demand for home heating exceeds gas production, injected gas is withdrawn from storage to make up the difference.

5) Responsiveness: how quickly markets react to changes in price or other market conditions

In Canada and the U.S., the oil and gas industry responds quickly to prices. Inadequate supply causes gas prices to increase, resulting in more drilling to produce more gas. Conversely, high levels of supply result in lower prices and less drilling. When it comes to LNG, low North American prices makes exporting overseas attractive, but exporters must still find viable markets. In recent years, a large amount of competing supply has flooded global LNG markets and lowered LNG prices, resulting in only one out of dozens of possible Canadian LNG projects moving towards construction.